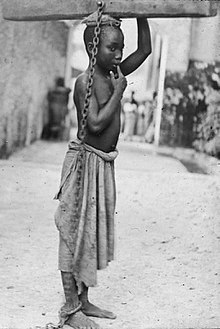

Photograph of a slave boy in Zanzibar. ‘An Arab master’s punishment for a slight offence. ‘ c. 1890 (photograph ourtesy Wikipedia)

By Spencer D Gear

Claims are made that the Bible supports slavery and that the people of contemporary culture should be able to choose their own values. Here are a few examples of such statements:

- ‘If you are truthful to the Bible, would you not agree with me that St Paul supports slavery while we today are dead opposed to it? That morality even in the Bible has changed?’ (Greneknight #64, Christian Forums, 22 August 2012)

- ‘Except for murder, slavery has got to be one of the most immoral things a person can do. Yet slavery is rampant throughout the Bible in both the Old and New Testaments. The Bible clearly approves of slavery in many passages, and it goes so far as to tell how to obtain slaves, how hard you can beat them, and when you can have sex with the female slaves. Many Jews and Christians will try to ignore the moral problems of slavery by saying that these slaves were actually servants or indentured servants. Many translations of the Bible use the word “servant”, “bondservant”, or “manservant” instead of “slave” to make the Bible seem less immoral than it really is. While many slaves may have worked as household servants, that doesn’t mean that they were not slaves who were bought, sold, and treated worse than livestock (‘Slavery in the Bible’, Evil Bible.com).

- ‘If the Bible is written by God, and these are the words of the Lord, then you can come to only one possible conclusion: God is an impressive advocate of slavery and is fully supportive of the concept.

If you are a Christian, I realize that what I am about to suggest is uncomfortable. However, it is crucial to the conversation that we are having in this book. What I wish to suggest to you is that these pro-slavery passages in the Bible provide all the evidence that we need to prove that God did not write the Bible. Simply put: there is no way that an all-loving God would also be a staunch supporter of slavery.

What does your common sense tell you about God? Doesn’t it seem that an all-loving, just God would think of slavery as an abomination just like any normal human being does? If any sort of all-knowing, all-loving God had written the Bible, shouldn’t the Bible say, “Slavery is wrong — you may have no slaves”? Shouldn’t one of the Commandments say, “thou shalt not enslave”?’ (Why does God love slavery?)

A glimpse into the Old Testament view

In the Old Testament, there were at least 6 ways in which a person could become a slave:

- As a captive of war: Num 31:7-35 (ESV); Deut 20:10-18 (ESV); 1 Ki 20:39; 2 Chron 28:8-15);

- They could be purchased. Foreigners could be purchased and sold and were considered property: Lev 25:44-46 (ESV); Ex 21:16; Deut 24:7. The OT gives examples of a father selling his daughter (Ex 21:7; Neh 5:5); children of a widow were sold to pay her husband’s debt (2 Kings 4:11); men and women sold themselves into slavery (Lev 25:39, 47; Deut 15:12-17).

- Bankruptcy (Ex 21:2-4; Deut 15:12);

- A gift of a slave could be given as Leah received Zilpah as her slave (Gen 29:24).

- As an inheritance: Lev 25:46 (ESV). Those who were not Hebrews could be slaves from generation to generation.

- Those slaves from birth (Ex 21:4; Lev 25:54) (This material is based on Rupprecht 1976:454-455.)

Slavery was widespread in the secular and Hebrew world of the Near East. For the Hebrews, there were regulations concerning the release of slaves (see Ex 21:1-11; Lev 25:39-55; Deut 15:12-18). Slaves were to be freed after serving for 6 years.

For the Hebrews, the slaves were members of the household and were included with the group of women and children (Ex 20:17).

In Gal 4:1, Paul states, ‘the heir, as long as he is a child is no different from a slave, though he is the owner of everything’. When we go to Gal 4:7 we discover, ‘So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God’.

There are some interesting and challenging dimensions to slavery when we compare the OT and NT material.

How should we respond to these allegations?

The following is how I responded to Greneknight, as OzSpen #65, 22 August 2012.

There are some excellent assessments and I do not plan to regurgitate what others have said. See:

- Brian Tubbs article online, ‘Was the Apostle Paul Pro-Slavery? Yes – but Not in the Way You Might Think!’

- Hard Sayings of the Bible, ‘Exodus 21:2-11, Does God Approve of Slavery?

- Rich Deem, ‘Does God approve of slavery according to the Bible?’

- Daniel B. Wallace, ‘Some initial reflections on slavery in the New Testament’;

- CARM, ‘Why is slavery permitted in the Bible?’

Concerning ‘1 Corinthians 7:17, 20 Remain in Slavery?’ (Hard Sayings of the Bible 1996. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, pp. 591-593), this writer’s assessment was:

The difficulty with which 1 Corinthians 7:17 and 20 present us arises primarily from the surrounding verses in the paragraph (1 Cor 7:17-24). In 1 Corinthians 7:21 the situation chosen as an illustration is that of slavery. In 1 Corinthians 7:17 the various situations in which persons found themselves when they were called to faith in Christ are understood as assigned or apportioned by the Lord, and they are told to remain in those situations. That instruction is given further weight in the sentence “This is the rule I lay down in all the churches” (1 Cor 7:17).

In light of these statements, Paul has often been charged not only with failure to condemn the evil system of slavery, but indeed with abetting the status quo. These charges can be demonstrated to be invalid when the paragraph which contains this text is seen within the total context of 1 Corinthians 7 and in light of the historical situation as Paul perceived it.In 1 Corinthians 7 Paul is dealing with questions about marriage, the appropriate place for sexual expression, the issue of divorce and remarriage, all in response to a pervasive view in the church which rejected or demeaned the physical dimension of male-female relationships. In the immediately preceding paragraph (1 Cor 7:12-16), Paul’s counsel to believers who are married to unbelievers is twofold: (1) If the unbelieving partner is willing to remain in the marriage, the believer should not divorce (and thus reject) the unbelieving partner; for that person’s willingness to live with the believer may open him or her to the sanctifying power of God’s grace through the believing partner (1 Cor 7:12-14). (2) If the unbeliever does not want to remain in the union, he or she should be released from the marriage. Though the partner may be sanctified through the life and witness of the believer, there is no certainty, especially when the unbeliever desires separation (1 Cor 7:15-16).

Having recognized the possibility, and perhaps desirability, of this exception to his general counsel against divorce, Paul reaffirms what he considers to be the norm (“the rule I lay down in all the churches”): that one should remain in the life situation the Lord has assigned and in which one has been called to faith (1 Cor 7:17). In light of exceptions to general norms throughout this chapter, it is probably unwise to take the phrase “the place in life that the Lord has assigned” too literally and legalistically, as if each person’s social or economic or marital status had been predetermined by God. Rather, Paul’s view seems to be similar to the one Jesus takes with regard to the situation of the blind man in John 9. His disciples inquire after causes: Is the man blind because he sinned or because his parents sinned (Jn 9:2)? Jesus’ response is essentially that the man’s blindness is, within the overall purposes of God, an occasion for the work of God to be displayed (Jn 9:3).

For Paul, the life situations in which persons are encountered by God’s grace and come to faith are situations which, in God’s providence, can be transformed and through which the gospel can influence others (such as unbelieving partners).

The principle “remain in the situation” is now given broader application to human realities and situations beyond marriage. The one addressed first is that of Jews and Gentiles (1 Cor 7:18-19). The outward circumstances, Paul argues, are of little or no significance (“Circumcision is nothing and uncircumcision is nothing”). They neither add to nor detract from one’s calling into a relationship with God, and therefore one’s status as Jew or Gentile should not be altered. (It should be noted here that under the pressure of Hellenization, some Jews in the Greek world sought to undo their circumcision [1 Maccabees 1:15]. And we know from both Acts and Galatians that Jewish Christians called for the circumcision of Gentile Christians.)

Once again, it is clear that the general norm, “remain in the situation,” is not an absolute law. Thus we read in Acts 16:3 that Paul, in light of missionary needs and strategy, had Timothy circumcised even though Timothy was already a believer. Paul’s practice in this case would be a direct violation of the rule which he laid down for all the churches (1 Cor 7:17-18), but only if that rule had been intended as an absolute.

Paul now repeats the rule “Each one should remain in the situation which he was in when God called him” (1 Cor 7:20), and applies it to yet another situation, namely, that of the slave. Paul does not simply grab a hypothetical situation, for the early church drew a significant number of persons from the lower strata of society (see 1 Cor 1:26-27). So Paul addresses individuals in the congregation who were of the large class of slaves existing throughout the ancient world: “Were you a slave when you were called?” (that is, when you became a Christian). The next words, “Do not let it trouble you,” affirm that the authenticity of the person’s new life and new status as the Lord’s “freedman” (1 Cor 7:21-22) cannot be demeaned and devalued by external circumstances such as social status.

As in the previous applications of the norm (“remain in the situation”), Paul immediately allows for a breaking of the norm; indeed, he seems to encourage it: “although if you can gain your freedom, do so” (1 Cor 7:21; note the RSV rendering: “avail yourself of the opportunity”). As footnotes in some contemporary translations indicate (TEV, RSV), it is possible to translate the Greek of verse 21 as “make use of your present condition instead,” meaning that the slave should not take advantage of this opportunity, but rather live as a transformed person within the context of continuing slavery. Some scholars support this rendering, since it would clearly illustrate the norm laid down in the previous verse. However, we have already noted that Paul provides contingencies for much of his instruction in chapter 7, and there is no good reason to doubt that Paul supported the various means for emancipation of individual slaves that were available in the Greco-Roman world.

And yet, Paul’s emphasis in the entire chapter, as in the present passage, is his conviction that the most critical issue in human life and relations and institutions is the transformation of persons’ lives by God’s calling. External circumstances can neither take away from, nor add to, this reality. The instruction to remain in the situation in which one is called to faith (which Paul repeats several more times, in 1 Cor 7:24, 26, 40, and for which he also grants contingencies, in 1 Cor 7:28, 36, 38) can be understood as a missiological principle. To remain in the various situations addressed by Paul provides opportunity for unhindered devotion and service to the Lord (1 Cor 7:32-35), or transforming witness toward an unbelieving marriage partner (1 Cor 7:12-16), or a new way of being present in the context of slavery as one who is free in Christ (1 Cor 7:22-23).

The transforming possibilities of this latter situation are hinted at elsewhere in Paul’s writings. Masters who have become believers are called on to deal with their slaves in kindness and to remember that the Master who is over them both sees both as equals (Eph 6:9). The seeds of the liberating gospel are gently sown into the tough soil of slavery. They bore fruit in the lives of Onesimus, the runaway slave, and Philemon, his master. The slave returns to the master, no longer slave but “brother in the Lord” (Philem 15-16).

Note too that the three relational spheres which Paul addresses in 1 Corinthians 7–male-female, Jew-Gentile (Greek), slave-free–are brought together in that high-water mark of Paul’s understanding of the transforming reality of being in Christ: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28). As a rabbi, Paul had given thanks daily, as part of the eighteen benedictions to God, that he had not been born as a Gentile, a slave or a woman. It was his experience of Christ that led him to recognize that these distinctions of superior and inferior were abolished in the new order of things inaugurated in Christ. Surely in this vision the seeds were sown for the ultimate destruction of slavery and all other forms of bondage.

Finally, Paul’s understanding of the historical situation in which he and the church found themselves provides another key for his instruction that believers should remain where they are. He, together with most other Christians, was convinced that the eschaton, the climax of God’s redemptive intervention, was very near. Statements in 1 Cor 7:26 (“because of the present crisis”) and 1 Cor 7:29 (“the time is short”) underline that conviction. This belief created a tremendous missionary urgency. The good news had to get out so that as many as possible could yet be saved (see 1 Cor 10:33). This expectation of the imminent end was surely an important factor for the Pauline norm “remain where you are.”

The biblical view of slavery might be wrong in the estimation of some contemporary Christians, but God did not have such a view when he breathed out the Scriptures (2 Tim. 3:16-17).

Response to the allegations against the Bible and slavery

There is an eerie silence by Jesus, the apostles and Paul in regard to rejecting slavery in a society. I would have thought that Jesus, the sinless Son of God, should have been condemning slavery outright – racial slavery like that in the USA — but this was not so. Why?[1]

- Please don’t assign a barbaric, violent, unjust view of slaves to the Romans. Paul’s word to slave masters was that they should treat slaves with kindness and consideration (Eph. 6:9; Col. 4:1).

- Slavery had become a well-known way to become a Roman citizen throughout the Empire;

- One study found that between 81-49 BC, “500,000 slaves were freed [by the Romans] during this period” and the city of Rome’s population was about 870,000.[2]

- In the Roman Empire, a slave could expect freedom in about 7 years.

- “When a master freed his slave, he frequently established his freedman in a business and the master became a shareholder in it.”[3]

- “While an individual was a slave, he was in most respects equal to his freeborn counterpart in the Graeco-Roman world, and in some respects he had an advantage. By the first century A.D. the slave had most of the legal rights which were granted to a free man.”[4]

- “Living conditions for most slaves were better than those of free men who often slept in the streets of the city or lived in very cheap rooms.”[5]

- “The free laborer in NT times was seldom in better circumstances than his slave counterpart.”[6]

- “In fact, in time of economic hardship it was the slave and not the free man who was guaranteed the necessities of life for himself and his family.”[7]

Islam and slavery

Do not confuse the Christian view of slavery in the Old and New Testaments with the contemporary view of ‘Islam & Slavery’ (Barnabas Fund). That article provides this conclusion:

Many Muslims agree that there is no place for slavery in the modern world, but there has as yet been no sustained critique of the practice. The difficulties and dangers of confronting the example of Muhammad and the teaching of the Qur’an and sharia (which most Muslims believe cannot be changed) have dampened any internal debate within Islam. Although slavery still exists in many Islamic countries, few Muslim leaders show remorse for the past, discuss reparations or show that repugnance for the scourge of slavery that eventually led to its abolition in the West. It is time for Muslims emphatically and publicly to condemn the practice of slavery in any form and to ensure that their legal codes An enslaved Pakistani Christian boy supporting it are changed.

Conclusion

I do not subscribe to the relativistic presuppositions of cultures determining their own values. I have too high of a respect for the Lord God Almighty and His Scriptures to secede to that view. This is what the Scriptures state:

- Isaiah 5:20, ‘ Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter!’ (ESV)

- Psalm 111:7-8, ‘The works of his hands are faithful and just; all his precepts are trustworthy; they are established for ever and ever, to be performed with faithfulness and uprightness’ (ESV).

- Proverbs 3:5, ‘Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding’.

- Ecclesiastes 12;13, ‘Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the duty of all mankind’ (NIV).

- John 17:17, ‘Sanctify them in the truth;your word is truth’ (ESV).

- 1 Peter 1:25, ‘The word of the Lord remains for ever’ (ESV)

- James 2:12, ‘Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom’ (NIV)

Notes:

[1] The following is based on the article by A. Rupprecht, ‘Slave, Slavery’, in Merrill C. Tenney gen. ed. 1976, Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible, vol. 5, Q-Z, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, Michigan, pp. 453-460.

Copyright © 2014 Spencer D. Gear. This document last updated at Date: 29 October 2015.